A long history

In 1923 Huda Shaarawi became the first president of the Egyptian feminist Union. Although women’s movements and groups have flourished in the region since the Shaarawi’s time, there has been very little change in the actual conditions and status of women. As this 2011 Amnesty International Report highlights nearly a century later women in the Middle East and North Africa are still facing “discriminatory laws and deeply entrenched gender inequality.” Indeed, the report goes on to say that “Across the region, women generally have lower levels of education and higher levels of poverty, and are grossly under-represented in the corridors of power.”

Women’s movements under authoritarianism

Rather than religious interpretations or cultural norms, the most important reason for the lack of progress with women’s rights in the Middle East and North Africa is that until the momentous events of early 2011, all the states in the region were characterised by authoritarianism (and most remain so). Totalitarian leaders dominated their societies so completely that women’s movements have been denied the autonomy and independence needed to push for a meaningful change in the lives of women.

Due to the nature of authoritarian politics women’s groups were not able to develop as mass movements with power bases and popular support but rather had to focus on advocating leaders, or even first ladies, to introduce reforms. In most cases, this enabled them to gain only small changes that were often little more than fig leaves for the problems faced by Middle Eastern and North African women.

Women’s rights under a dictator: The case of Egypt

Any changes that were made tended to benefit presidents and monarchs more than women. For example, in early 2010 Hosni Mubarak introduced a quota of 64 seats for women MPs (out of 508 – about 12%) in the Egyptian parliament. Though a positive step in itself, every single quota seat went to members of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party which not only limited the effect of the reform but delegitimised the very notion of a quota for female MPs in the eyes of the Egyptian public.

Not only are such reforms limited but any gains they did achieve were inherently vulnerable as they are dependent on the goodwill of the leader and can be easily reversed if circumstances change. For example, in the 1970s lobbying of former Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s wife Jihan led to some minor reforms of the Egyptian personal code. However, when Sadat was replaced by Hosni Mubarak, ‘Jihan’s laws’ left with him. Thirty years later when Egyptian revolutionaries, many of whom were women, overthrew Mubarak, the reforms associated with his wife Suzanne are now under threat, tainted with being tied to the former regime and without a dictator to uphold them.

This dynamic was not only present in Egypt but in almost every state in the region. For example, in Libya Qaddafi’s domination (along with his daughter Aisha) of the women’s movement was so absolute that it has been referred to as ‘state feminism’ under which some progressive changes are introduced but entirely at the whim of the leader and his inner circle and often only for show. Similarly, Ben Ali sought to actively exploit Tunisia’s relatively good women’s rights record in order to provide international cover for broader human rights violations.

Trying to resist authoritarianism: The case of Morocco

This is not to say that women’s movements in the MENA region have not tried to overcome this problem. In 2000 a coalition of women’s groups in Morocco launched a million-signature-campaign to introduce a new family law (moudawana) in the kingdom. In order to avoid reinforcing the authoritarian nature of Moroccan politics, they presented their petition and proposals to Morocco’s elected parliament. However, the plans were blocked as parliament lacked the ability to carry forward the reforms in the face of conservative opposition. The lesson learnt was that there was no point in the women’s movement seeking to mass mobilize and introduce reforms through democratic channels.

Four years later, the same coalition decided to bypass parliament and presented the reforms directly to the king, Mohammad VI. Within two months a slightly diluted version of the proposals became law “in the name of the king”. The reforms, and the women’s movement as a whole, were now dependant on and indebted to Mohammad VI. A victory had been won but at the cost of a powerful women’s movement that could continue to push for and maintain women’s rights autonomously – including the constant application of the new law.

Half a revolution?

With the changes that have taken place in the region over the past year, there has been much disappointment with regards to women’s rights. In fact, there are far less female MPs in Egypt now than there were under Mubarak, women have been largely excluded from the Transitional National Council in Libya, and women have made little gains in Tunisia.

This is largely due to the fact that the respective women’s movements lack the power to take advantage of the political vacuum created by the fall of regimes during the Arab Spring. It should come as no surprise that women’s groups have been slow to effectively organise in the aftermath of the revolutions as under former regimes organising was either not permitted or redundant.

As a result of the nature of authoritarian politics women’s groups were pushed into strategies of concentrating on advocating authoritarian leaders as this was the only realistic means for achieving reforms. As such there was little incentive, let alone opportunity, for mass-mobilization or building-power bases.

Optimism for the future?

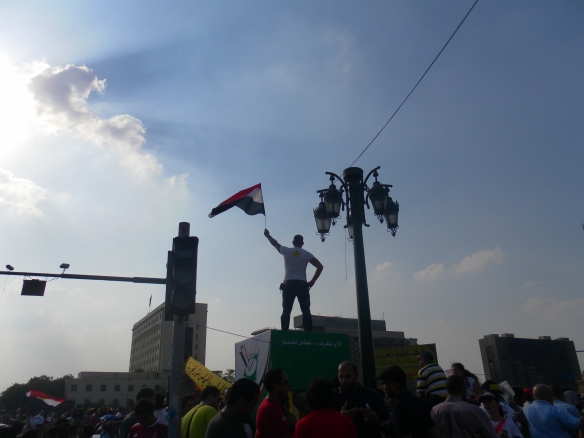

Nevertheless, following the Arab Spring revolutions, there is hope that this pattern can be broken and in the long term real changes can be made in the transitional states. In Egypt, for example, women have shown that they can be mobilized en masse, with vast numbers of women coming out to vote in Egypt’s recent parliamentary elections.

With authoritarian regimes removed, women’s groups can now mobilize popular support behind their causes and, once democratically elected governments become dependent upon their support for re-election, there is finally the possibility that real and meaningful changes will be introduced.

For this to happen it is essential that civil society organisations, and in particular the women’s movements and women human rights defenders, are given the space to campaign freely, effectively, and independently for women’s human rights. This is why it is so important to ensure that the new regimes respect freedom of association and the rights of activists.

AIUK event

Want to show your solidarity with women’s human rights defenders in the Middle East? Come to Amnesty International UK’s panel event on 20th March at 7pm to hear activists from Egypt, Libya, and Iran speak.